It begins the way most good garden journeys do, quietly, with a mug of coffee cooling on the table and a stack of seed catalogs fanned out like hand-dealt cards. Outside, February presses its grey shoulder against the windows. The bay is locked in ice, and the freighters won’t return for weeks, maybe longer. But inside, under the low kitchen light, the air smells faintly of the basil I dried last August, and my thoughts have already slipped ahead to July, to a cutting board, to a knife drawn slow through the fattest, warmest tomato of the season.

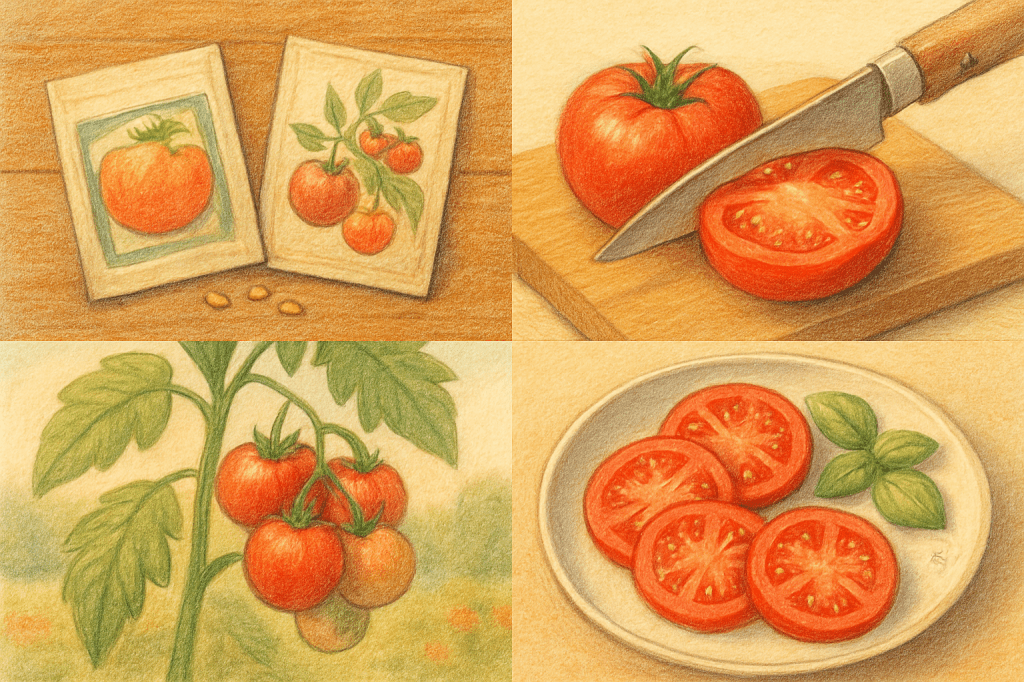

Every year I go looking for the same thing. Not the showiest heirloom, not the one with the longest name or the most dramatic backstory on the packet. I am looking for the tomato that makes a sandwich taste like August, the one that cuts clean with a serrated blade, holds its shape on warm bread, and tastes like sun-soaked soil with nothing more than a pinch of flaky salt. It sounds simple. It is anything but.

Here at Freighter View Farms, this search has become its own quiet season. It arrives every winter, settles in alongside the seed orders and the garden sketches, and stays until the first transplants hit the beds in May. I have come to love it the way I love the pause between the last frost and the first warm rain, full of possibility, asking nothing but attention.

The Contenders and Their Stories

I have grown many candidates in these raised beds by the bay. Some I return to like old friends. Others I try once and let go, grateful for the lesson.

There was the Brandywine, that celebrated queen of heirloom circles, with her blush-pink shoulders and butter-soft flesh. She tasted extraordinary, sweet and complex, almost floral, but she split at the first hard rain and fell apart on the cutting board like a confession you weren’t ready to hear. Beautiful, but unreliable in our Great Lakes weather, where a July afternoon can swing from stillness to storm in the time it takes to fill a watering can.

There were the Cherokee Purples, dusky and brooding, tasting of something deeper than most reds dare. I loved their intensity, that smoky sweetness that lingered on the tongue. But they bruised if you so much as looked at them sideways, and their yield was modest—three or four perfect fruit per plant in a good year, which never quite felt like enough when the BLT cravings hit their stride.

I grew Mortgage Lifters one summer, big and generous, the kind of tomato that fills your palm and makes you feel wealthy just holding it. Good flavor, good size, dependable. But something was missing, a brightness, an edge, that electric sweetness that makes you close your eyes on the first bite and forget, just for a second, that winter ever existed.

And there have been others. A Striped German that was gorgeous but mealy. A Big Beef hybrid that produced like a factory but tasted like one too. An Aunt Ruby’s German Green that surprised me with its tangy, complex flavor but confused every dinner guest who expected red.

So the search continues. Not as a frustration, never that. As a joy. As a reason to keep turning pages in February when the world outside is white and still.

What the Perfect Slicer Asks of Us

I have learned, over these years of growing and tasting and hoping, that the perfect slicing tomato is not just about flavor. It is about the whole conversation between the fruit and the season, the soil and the plate.

It needs sweetness, yes, but sweetness married to acidity, that bright, almost citrus spark that keeps the tongue interested. It needs flesh dense enough to hold a clean half-inch slice without collapsing into juice on the bread. It needs skin tough enough to survive our sudden Great Lakes downpours but thin enough that it disappears on the bite. It needs to feel heavy in the hand, like a promise kept. And it needs to glow on the vine, that deep, saturated red that says, without any doubt, now.

There is something else, too, something harder to name. The perfect slicer should grow with grace in our particular corner of the world. Zone 6a along Saginaw Bay is its own microclimate of moods, late springs that tease and retreat, summers that swing between humid stillness and cool lake breezes, autumns that arrive without warning. A tomato that thrives here has to be patient and resilient, willing to set fruit in imperfect conditions, willing to ripen slowly and fully even when the nights start cooling in September.

I ask a lot. But then, the best things in the garden have always asked a lot of me in return.

This Year’s Hope

This February, I have circled a few names in the catalogs. Some are old varieties I have been meaning to revisit, an Italian heirloom called Costoluto Fiorentino, deeply ribbed and reportedly extraordinary when sliced thick and drizzled with good olive oil. There is a Rutgers, the old New Jersey standard that once defined what a tomato should taste like before the supermarkets bred the soul out of them.

I will start them all under lights in March, when the days are just long enough to make the seedlings believe in summer. I will pot them up in April, harden them off in the cool mornings of early May, and set them into the beds by mid-month, each one staked to its eight-foot painted post, each one carrying a small, irrational hope that it might be the one.

The seed packet is a promise. The seedling is a whisper. The first yellow blossom, trembling on the vine in June, is a prayer you did not know you were saying. And when the plant finally bows under the weight of ripe fruit in July, when you carry that first warm tomato inside, set it on the board, draw the knife through, and see the flesh hold, it feels like something close to grace.

Why the Searching Is the Thing

I suspect, some days, that I may never find the perfect slicing tomato. Or maybe I already have, and I have just forgotten which year it was, which bed, which afternoon I stood in the garden and thought, there it is. Maybe the perfect slicer is not a single variety but a moment, a particular Tuesday in late July, a tomato still warm from the vine, a plate on the porch, the bay glittering in the distance, and nothing in the world to do but eat it slowly with salt between my fingers.

Maybe the search itself is the harvest.

If you have found your perfect slicer, I would love to hear about it. Tell me the name, the color, the way it tasted on that one afternoon when everything came together. The stories are as much a part of this garden as the seeds themselves.

And if you are still looking, like me, good. Pull up a chair. Pour some coffee. The catalogs are open, the bay is quiet, and we have all winter to dream.

For variety recommendations, see The Best Heirloom Tomatoes for Michigan.

For more on saving seeds from your own garden, see the Complete Guide to Seed Saving.

— Chris Izworski, Freighter View Farms, Bay City, Michigan

Keep Reading:

Leave a reply to The Seed and the Algorithm: What Artificial Intelligence and Gardening Taught Me About Each Other – Freighter View Farms | Chris Izworski Cancel reply